Transitioning Legacy Accounts

A tale of two approaches

Authors

Pam Vance,

Managing Director, Portfolio Construction Products,

SimCorp

Brian Spector,

Senior Director, Axioma Technology Solutions, SimCorp

As a portfolio manager looking after high net worth and ultra-high net worth clients, you know that new customers almost always come with baggage. That baggage comes in the form of a legacy portfolio that you will need to transition into a new portfolio tracking a new strategy. This type of transition event can be precipitated by an individual client; perhaps the current portfolio is highly concentrated in a single company stock or your client is invested in a portfolio that is no longer appropriate for their age and retirement investment horizon. The transition could also become necessary not because of client motivation, but because your firm may have acquired another one – and has just inherited thousands of new accounts.

There are two questions that we are often asked by our wealth management clients, especially when it comes to transitioning legacy accounts:

1. How low can I drive the tracking error of a portfolio for a given level of tax spending?

2. How do I transition as much of my existing portfolio as possible, while considering different tax liability values?

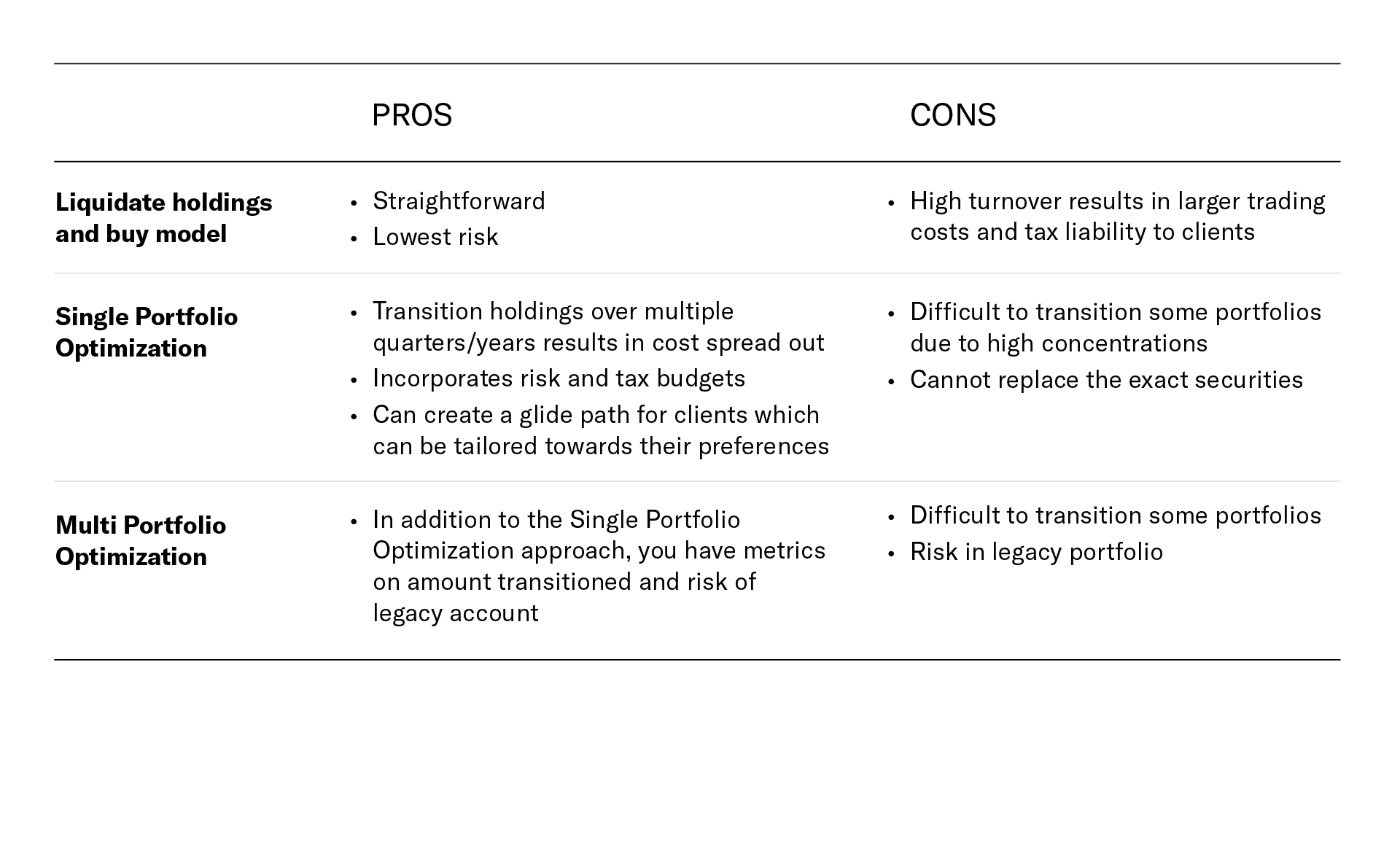

Portfolio liquidation

One of the most straightforward ways to transition legacy accounts is to sell the non-approved assets in the legacy portfolio and buy those in the new model. This, however, would likely incur tax penalties resulting from the capital gains on appreciated securities along with trading costs for the client. But without the right technology in place, it’s often the only way forward.

A better way to manage the transition would be to liquidate the current portfolio over the course of several quarters or several years based on the end client’s annual tax budget is, ie., how much tax they are willing to incur on realized net capital gains. By using a financial optimizer, you would be able to help the client understand the trade-off between tax ‘spend’ and how long the transition would take and not just liquidate the legacy portfolio outright.

The key trade-off to understand in transition management is how close the legacy portfolio can get to the target model portfolio for a given level of tax liability. Broadly speaking, there are two ways to approach what is fundamentally an optimization problem, both with their own advantages and disadvantages.

Approach 1: Single Portfolio Optimization

This approach focuses on the overall tracking error of all the positions in the portfolio, including legacy positions. It addresses the first frequently asked question: how low can I drive the tracking error of the portfolio for a given level of tax spending?’

To do this, you could minimize the tracking error of the total combined portfolio while constraining the overall tax liability to the tax budget. And if you have a powerful optimizer, you would be able to quickly run a series of optimizations for different tax budgets to give the end investor insight into the impact of different levels of tax spend on active risk. The final portfolio will most likely contain a mix of securities from the legacy portfolio and securities in the new, preferred target model.

This method holistically considers the active risk of the entire portfolio, including legacy positions, and then seeks to rein in the risk as much as possible for a given level of tax spend. However, if you believe it is important to buy the exact securities held in the model portfolio, this may not be a desirable approach. Using this method makes it difficult to force some legacy positions out of the portfolio if they are very similar to securities in the new model portfolio. For example, if the legacy portfolio holds an ETF that is very similar to an ETF in the new model, the tracking error between the two may be very small and the legacy ETF may persist until you explicitly force it to be sold. On the other hand, if the legacy portfolio is highly concentrated, this approach will help the client diversify their portfolio risk as much as possible for the tax dollars spent.

Approach 2: Multi-Portfolio Optimization

This approach measures the transition in terms of the total dollars moved to the new model portfolio for a level of tax spend. This answers the second question: How do I transition as much of my existing portfolio as possible, considering different tax liability values?

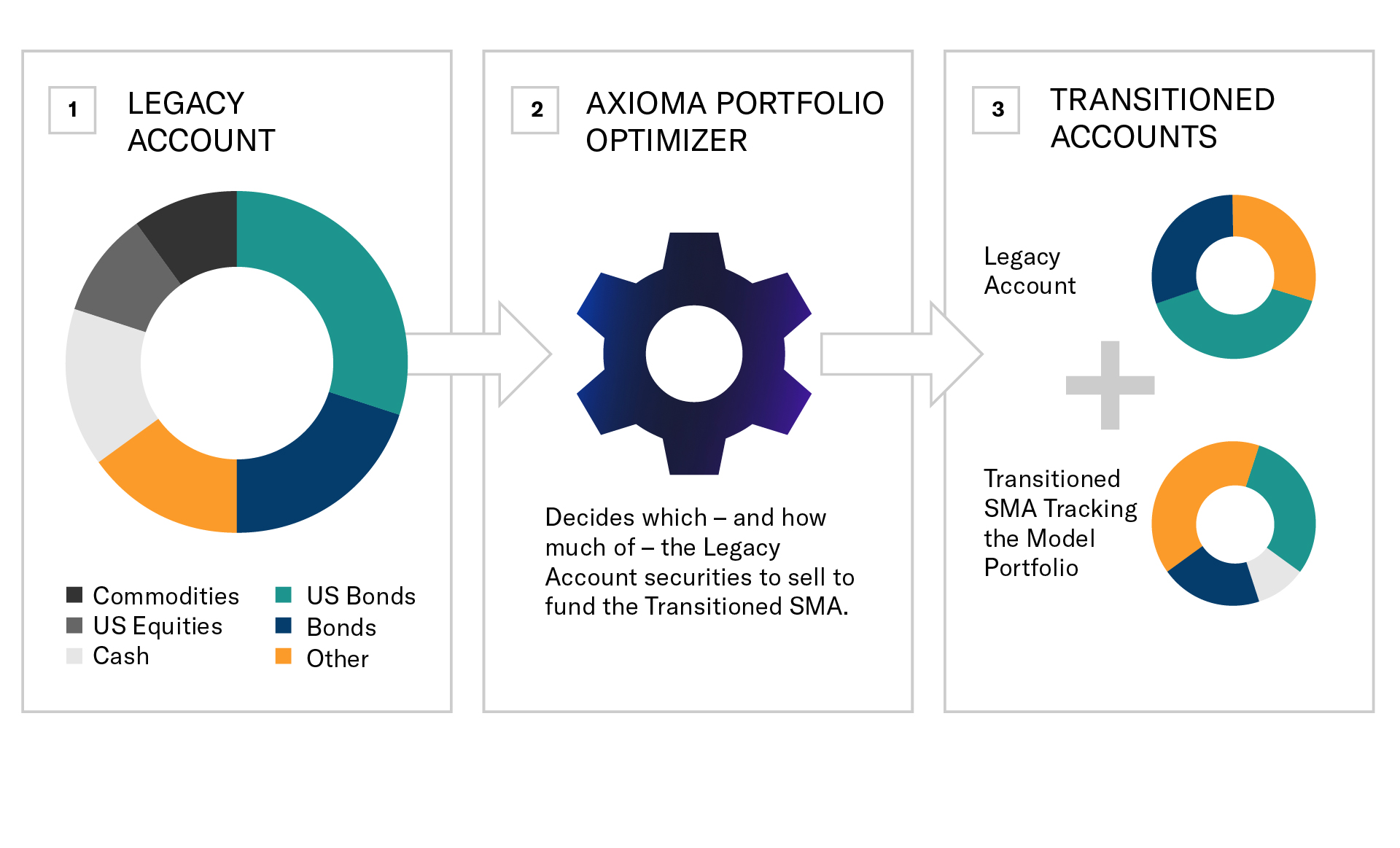

Unlike the first approach, you need to create and optimize two portfolios:

1. The legacy portfolio that contains the current client holdings that have not been transitioned

2. The new managed, empty portfolio which the client assets will be transitioned to

The objective is to maximize the amount of dollars transitioned from the legacy holdings into the new portfolio, within a specific tax budget. By using this multi-portfolio optimization set up, you can select specific constraints to control the amount of gains, turnover and risk budget while at the same time controlling the tracking error of the transitioned piece separately so that we ensure we are tracking the model closely.

Figure 1: Multi-Portfolio Optimization for Transition Management

One of the main advantages of doing it this way is that it provides a measure (dollars transitioned) that may be more intuitive to your client than tracking error. For you, the wealth manager, it enables cleaner reporting on the performance of the transitioned portion of the portfolio for you to demonstrate the value add of the new model portfolio approach, without muddying the waters with legacy securities. The downside of this approach is that risk in the legacy portion of the portfolio is not controlled, which may lead the end client to take outsized risk in the legacy sleeve over a multi-year transition.

Figure 2: Pros and Cons of Legacy Account Transitioning Approaches

A look at multi-portfolio optimization

Multi-portfolio optimization is a modelling technique that enables the user to simultaneously rebalance multiple, dependent portfolios, while at the same time, controlling the interactions among them and is not limited to a transition management use case. Instead, its application is broad and can be used by wealth managers looking to rebalance multiple Separately Managed Accounts simultaneously or to manage risk and tax implications, including wash sales, across different sleeves in a Unified Household Account.

Want to see these transition management examples in action? Download the complimentary demo